INTRODUCTION

By Steve Kettmann

My first reaction was to be mad at Bob Nightengale for calling on a Sunday evening. My six-year-old daughter, Coco, had just made herself a salad, start to finish, for the first time, gathering the miner’s lettuce herself, washing and spinning it, mixing up a dressing of olive oil, lemon and honey. We were at the kitchen table and Coco was raising her fork. Just then Bob texted. And called. And texted again. I tried to ignore him, so I could focus on sharing this little milestone with Coco. A voice inside my head wouldn’t let me: The Gomez Rules did not allow it.

Bob and I had in common a great friend named Pedro Gomez, and if another friend of Pedro’s called and wanted something, the rules were clear: You picked up. Maybe Bob, a USA Today baseball writer, needed my help on something. Maybe it was about Pete Rose or Jose Canseco. I’d worked closely with both on book projects. So I called Bob back and will never stop hearing the catch in his voice as he asked me, “Are you sitting down?” Then Bob told me that Pedro had died, suddenly, at home in Ahwatukee, Arizona, shortly before the Super Bowl. He was fifty-eight.

I immediately called Pedro’s wife, Sandi, and we talked in hushed, shocked voices for a while. For me as for so many others who loved Pedro, his death hit first as the story of a husband and father, a man who always talked about “hitting the Lotto” in marrying the love of his life, Sandi, and a proud father who talked constantly about his three children, Rio, Dante and Sierra. The first ripple of pain came with knowing what a void his loss would leave in their lives.

Then came the selfish part of grief, for so many of us, the feeling of having a part of ourselves ripped away. It was as if a vital organ had suddenly been lost that channeled our capacity for joy and enthusiasm for life. Pedro was in love with life and in love with all his friends. He made sure you felt that, every time you connected. That was true if you’d met him once years ago or, like me, been one of his best friends for decades. (“It’s your wife!” Sandi would kid Pedro when I called the house yet again in the ’90s.)

“It’s odd to lose a very close friend, to see his death ripple out to millions, and to come to understand that for many of them, this was a deeply painful loss as well.” — Steve Kettmann

It’s hard to pull many recollections from the deep fog of those first days after the stunning news, but at some point that week my wife, Sarah, and I packed up our 2003 Honda Accord, snapped Coco and Anaïs into their car seats, and set off for an eleven-hour drive to see Sandi and the family in Arizona. Along the way the scenes kept flashing at me. I thought of the time I decided to surprise Sarah for her birthday by taking her to Tegel Aiport in Berlin, where we lived, without telling her we were flying to Venice. Two days into our stay, she ran into Pedro in the lobby of our hotel. He did his best to sell her on the idea he was surprised to see her. Obviously at some level she knew Pedro and I must have cooked this whole scenario up, all of us running into each other in Venice. But when Pedro sold something, he sold it all the way.

“No, what are you doing here?” Pedro kept repeating to Sarah in that small lobby, unleashing the full Gomez conviction and a blinding blizzard of charm. We laughed over that one the whole next day, during the requisite gondola ride, Sarah and Sandi and Pedro and me (hey, it was fun, even if Pedro “went Cuban” a little on the mouthy gondolier, as he himself put it with a shrug). Even years later, Pedro still loved to tell that story, laughing before he could start, one more greatest hit in the vast collection.

It’s odd to lose a very close friend, to see his death ripple out to millions, and to come to understand that for many of them, this was a deeply painful loss as well. Pedro brought people in baseball together in death as in life. When word spread on Super Bowl Sunday that Pedro had died, a thunder-clap of shock and grief shook nearly everyone in the game, sooner or later. Barry Bonds was among many who sent flowers.

I can tell you that right up until the end, Pedro was doing what he loved. He was, in fact, midsentence, telling a story, when the end came as he stood in his kitchen, not far from where the Super Bowl would be showing on his living-room screen, game time not far off. RIP PEDRO was soon trending on Twitter. The New York Times published an obit, memorializing Pedro as “A Pillar of Baseball Coverage for ESPN.” Emotional tributes proliferated, not only on ESPN—by in particular Shelley Smith and Rachel Nichols—but also in newspapers all over the country. (Only later did the autopsy reveal that the cause of death was “sudden cardiac arrest,” a detail left out of the first wave of coverage.)

For this book, we reached out to Max Scherzer, whose intensity on the mound Pedro compared to one of his all-time favorites, Dave Stewart, the ultimate embodiment of bringing everything you’ve got when the moment is biggest. I’d been hearing highlights of Pedro’s conversations with Max for years, and knew he’d be eloquent on Pedro. I’ll admit I’m a little blown away by the sweetness of his contribution, #7, “Have Fun Every Single Day.”

“Pedro saw baseball for what it was,” Max writes. “He never forgot how fun it was to go to a game. That was something I immediately gravitated towards. I loved that I could just sit there in front of my locker and talk to Pedro about baseball, and have it be such a delightful conversation because of his insight and his positive personality. Before you knew it you’d look up and see you’d already been talking for an hour.”

How would Max try to put into words what Pedro stood for? “Have fun every single day. Whoever you come across, try to find the good in people. And when you find good people, talk to them even more. I feel like that’s what Pedro did. He understood who the good eggs were and who the bad eggs were. When you find a good egg, make sure that you always go in depth and you can talk about anything. Building those human relationships is worth more than one story’s clickbait.”

That open, alert quality of Pedro’s pulled him far beyond the limited universe of baseball, and sports more broadly. The story of Pedro in March 1999 returning to Cuba for the first time has now become familiar to many. We were there for a game between the Cuban National Team and the Baltimore Orioles, but Pedro had much more on his mind. Bob Ley, who might have launched ESPN as much as ESPN launched him, writes in his essay that “the most emotional interview” of Pedro’s thirty-seven-year career in newspapers and TV must have been on that visit with a former neighbor of his parents in the Havana neighborhood where he’d been conceived. Pedro’s parents were finally able to catch an Eastern Airlines flight to Miami to flee Fidel Castro’s regime in late July 1962, three months before the Cuban Missile Crisis—and three weeks before Pedro was born. His mother always told him about a strident communist neighbor who ridiculed his parents for their decision to leave. Pedro found that neighbor, Rodolfo Fernandez-Guzman, and talked to him about his parents, thirty-seven years later.

It was an astonishing tour de force of reporting, published in the Arizona Republic, and it’s widely remembered. Yet I don’t think most people are aware of the brave political stance Pedro also took on that first visit. I was there with him—I filed articles for Salon and the San Francisco Examiner— and the idea might have come up when Pedro and I were walking the streets of Havana, playing stickball with some kids using wadded-up tape as the ball in a Casa Blanca alleyway, or possibly during a long dinner in a private-home restaurant with a sumptuous view. I don’t remember. We talked about it for hours before Pedro decided to write a piece calling on the President of the United States to end the economic embargo of Cuba, a stance he well knew would cost him many friends back home in Miami and lead to countless arguments, Gomez at the center of a circle of worked-up Cuban friends or family members all chopping the air with their hands to make a point as they ganged up on him. (I was there in Miami for some of those later sessions, as a matter of fact, the presence of a longhaired comunista from Berkeley, as they saw me, only adding to the list of indictments to be read to their favored son who’d lost his way.)

Pedro, Sandi, Sierra, Rio, and Dante.

That Open Letter to Bill Clinton was printed on the cover of the Arizona Republic’s Arts & Ideas Section, which made Pedro very proud at the time, and we print it in full in this collection at #9. “For so many Cubans living in the United States, it is easy to stand on a platform and declare how the U.S. economic embargo must never be lifted as long as Fidel Castro remains in power,” Pedro wrote from Havana just before he and I watched a game in the stands at the Estadio Latinoamericano, maybe a dozen rows back from Fidel. “I am sympathetic to that point of view, having been raised with that idea. All I can say is that after talking to regular everyday Cubans, not the elite from the Communist Party, my feelings have changed dramatically.”

After Pedro had made the transition to TV and shown he was a natural, T.J. Quinn and I started working on him to run for Congress. We were serious, very serious. We told him we thought that sooner or later, growing Latin voter registration would help turn Arizona blue. Pedro had met both George W. Bush and John McCain on different occasions and respected both men. He came away from those encounters impressed with the warmth and genuineness of both, but Pedro was a Democrat all the way, as political strategist Paul Begala makes clear in his essay on his lively friendship with Pedro, almost all of it virtual.

Pedro, Paul writes, was a “darn good political strategist” who wrote Paul early in the Trump presidency that someone should dub him “President One Term.” “Pedro was prescient, of course,” Paul writes. “He was convinced from the start that Trump would be a one-term wonder. Just five months into Trump’s first year, Pedro saw the writing on the wall more clearly than most political pros.”

Pedro and I were both lucky to have many incredible mentors over the years, including Edvins Beitiks of the San Francisco Examiner, a man only Ray Ratto has the flair and fury to summon fully (Ray calls Beitiks a “keenly insightful bag of rumpled laundry” and a “weird oracle”— all true). I knew Pedro was a natural as a mentor to countless young journalists, and knew some of the stories, but only after we’d lost him did I begin to get a sense of the staggering scale of just how many lives he’d influenced in huge ways. Sarina Morales writes in her essay of idolizing Pedro, before they’d ever met, and of him helping her in her career, all the way to anchoring SportsCenter. Alden Gonzalez’s essay title says it all: “He Carved a Path for Me.”

Pedro’s death jolted baseball the way it did, I think, because in his death we all saw a thousand other deaths: our own, of course, for if a man so full of life and love could drop dead just like that, then of course all of us can, but also the death of dreams, the death of those careening and gleeful enthusiasms of youth, the vertiginous feel of unlimited possibility, which baseball can and should evoke, at least in the heart of a true fan.

“He was one who you really looked forward to running into, he had such a smart, wise take on things,” Joe Buck told me the week after Pedro died. “He was just gentle in a profession that now for some reason rewards the loudest voice in the room. He was the last guy to say, ‘Look at me.’ He was one of the true journalistically sound, integrity-filled people who just wanted to do the job.”

Pedro knew that if you let it, baseball could take you places, instill in you wonder and joy and most of all, an unforgettable sense of connection with others. He asked only that you be open to the moment, open-eyed and open-hearted, which was why his face twisted into a sucking-on-lemons scowl when he talked about “dead fish,” people who were only going through the motions. “He really doesn’t care about baseball,” Pedro told me in the final weeks of his life about one executive, a pronouncement that made Pedro deeply sad, like Obi-Wan wincing when he felt a weakening of the Force.

I think the outpouring after Pedro’s death had to do with more than just charm, more than just likability: Pedro truly did stand for something. He believed that baseball and other sports offered us a chance to be a little more human, a little more passionate, a little more tuned into the spice and variety and sheer crazy wonder of life’s randomness. He believed baseball and other sports could bring people together because he lived that for decades. He loved that feeling of standing on the field during a World Series, there at the center of the action, as wired into what was happening as anyone could be.

“I know for me he was the guy you wanted to see … when you came out on the field in the World Series,” AJ Hinch writes in his essay, a thought that inspired the cover art by Mark Ulriksen, who has more than fifty New Yorker covers to his credit.

Somewhere along that February 2021 drive to Arizona, as I flashed on different thoughts about Pedro, and turned over in my mind comments people had made comparing him to Anthony Bourdain and other largehearted people whose deaths hit especially hard, I started gravitating toward a comparison I knew would strike some as unlikely. I started thinking about what Pedro, first and foremost a baseball writer, had in common with the man so many of us consider the greatest baseball writer ever, Roger Angell.

The more I mulled it over, the more it seemed fair to conclude that Roger started something in February 1962 with his first New Yorker article on baseball that Pedro, as much as anyone else since, moved forward. From that first dispatch, “The Old Folks Behind Home,” Roger found a way to write about baseball that was all his own. He changed the sport, changed what it meant to be a fan by giving so many a vocabulary and palette through which to articulate a nuanced connection to so many facets of the baseball experience.

Pedro, proud son of Cubans, fluidly bilingual, ubiquitous presence on ESPN, gave the game a Latin face; he was suffused with the joy and passion of the Latin version of the game and always made sure it showed. For fans and for countless people in the game, Pedro was the ultimate connector, there to give a manager in a personal crisis a blunt dose of spot-on advice, there to reveal a human detail that reminded people not to obsess about launch angles and numerological metaphors, but to see baseball as a proving ground where character is made, unmade and revealed. Roger and Pedro were both, above all, fans of the game, secure enough in who they were to be utterly comfortable in the role of full-fledged enthusiast, exuberant and passionate fans unafraid of rapture, who also happened to be among the greatest reporters of their generations.

As Roger once explained his pursuit to me, “What I’ve been doing a lot of times is reporting. It’s not exactly like everybody else’s reporting. I’m reporting about myself, as a fan as well as a baseball writer.” Roger brought the emotional experience of the fan to life with such joy and detail and sweep, for example after Carlton Fisk’s memorable Fenway Park home run in Game 6 of the 1975 World Series, he created fans who had more of a connection to the game. That was what Pedro did over more than thirty-five years as a sportswriter and ESPN mainstay. He found a way to unlock secrets and insights about the people in the game that brought alive in fans at home the passion for baseball that burned in Pedro his entire life. All through it, he was never a guy in a role, but a warm personality people felt like they knew, a man whose take on things had to make sense since clearly this was someone who just about everyone liked—and everyone respected.

I remember when Roger and I were nearing completion on Game Time, a book of his baseball writing I conceived and edited. I spent the summer of 2002 in New York, flying in from Berlin, to sit with Roger every day and go through the New Yorker archives and mull over selections. This was in the Conde Nast Building on Times Square, gleaming and alive with potential. Roger and I were talking about his description of Troy Percival, the Angels’ closer, in a section new to the book, not previously published. Elsewhere, Roger had referred to Percival as “pallid and squinting,” and in this new section he called him “pale and musing.” Roger, deeply committed to nuance, had a rare qualm, and asked me if I thought he had Percival right. I told him I thought so. He stared at me, uneasy. Maybe I’d sounded unconvincing. Then I figured out a way to make him smile.

“Why don’t I call Pedro and get his take?” I suggested.

“Could you?” he answered quickly, noticeably relieved.

I could and I did. Pedro offered his take, rich in the credibility of all those years on the field, and Roger felt better. Writing this Introduction, I read back over the passage and was struck at how Roger’s words still feel urgent and relevant. “Fans and writers expect a lot of the players— we’re looking for the exceptional, every day, and great quotes after—and we’re in need of baseball archetypes, as well,” Roger wrote in “Penmen.” “The eccentric reliever has almost held his own here, while other familiar figures—the wise, white-haired manager; the back-country coach … and the boy-phenom slugger or strikeout artist—have been slipping from sight, smoothed into nullity by ESPN, Just for Men, the Bible, and tattoos.”

Ed Beitiks. Photo by Kim Komenich

Pedro was an Arizona Republic columnist at the time, but by the next year when Game Time was published, he had joined ESPN, where for eighteen years he waged a war against anyone smoothing baseball personalities into nullity. South Carolina basketball coach Frank Martin, close friends with Pedro back to their days as young dudes working in a Miami bank, explains in the leadoff essay of the collection, “Like a Mike Tyson Left Hook,” that Pedro’s dream was always to be a writer—and the TV work was an extension of Pedro the writer. Gomez asked only for a seat at the table, a voice to be heard along with so many great ball writers he revered, like Bruce Jenkins, Tim Keown and Dan Shaughnessy, or Ross Newhan, Peter Gammons and Ken Rosenthal, who all contribute essays, and so many others, from Len Koppett and Jerome Holtzman to Thomas Boswell and Claire Smith. Nothing gave Pedro more pleasure than ushering in fresh faces to the ranks of ball writers, showing them the way, as he showed Brian Murphy, who writes about covering the 1999 American League Championship Series with Pedro in essay #13, “Always Grab the Corks.”

I’ll come right out and say it: I think the world needs more people like Pedro Gomez. I think his love of life and love of getting to know people as they really are offer perspectives and insights that people might find valuable in their own lives, leaving aside what they might think about baseball and other sports. “Pedro sought authenticity the way a wildfire burns toward dry fuel,” Tim Keown writes in his essay, “Come On!” “He was a one-man rebellion, chiseling through the hagiography to get to whatever story lay buried inside.”

In putting together this essay collection, I’ve been acutely aware of how lucky I am to be able to reach out and share my grief with so many eloquent and passionate voices, who bring alive so many facets of Pedro, his life and his legacy, in these pages. Not everyone gets to mark the sudden passing of their best friend—or other loved one—by doing a turn as a Dream Team coach and assembling a lineup of All-Stars. Ed Beitiks hammered into both Pedro and me years ago that when it came to honoring the newly dead, you went all out. If not now, then when? In devoting a book to exploring why so many cared about Pedro Gomez, we hope also to make the larger point that we have to honor all our dead, tell their stories, clear space amid the static to reflect and mourn—and learn.

These essays can help people who knew Pedro—and people who did not—find more spark in their lives. They can also try to make up some of what we lost in not being able to mourn Pedro as we would have in non-pandemic times, crowding together to seek solace and maybe inspiration. The essays all, in their own way, carry a suggestion that maybe more people can try to be a little more like Pedro. Or more like who Pedro saw in them.

That was the thought I tried to convey when I stepped up to a microphone suspended over home plate at Salt River Fields in Phoenix for an invitation-only celebration of Pedro’s life on the Saturday six days after he died, all of us having been tested for Covid. Other friends had spoken, and the family members would speak next: Dante, Sierra and Rio, and then Pedro’s wife, Sandi.

Here are the words I shared that day:

“REMEMBER WHO YOU ARE”

I keep waiting for another text from Pedro. A call. A voicemail to make my day. So many of us feel that—like we’ve lost a part of ourselves. Our hearts don’t just hurt, they feel deflated. What does it take in a person to inspire so many to feel so strongly and with such urgency?

Eleven days ago, Pedro called me when I was live on Zoom for a virtual book event. I couldn’t pick up, but after that it was like Pedro had entered the Zoom conversation. Swear to god. A participant who earlier referred to me as “Kettmann,” my name, suddenly started calling me “Ketterman.” Not once. Several times. It was like he was channeling Pedro. For twenty-five years, Pedro has been calling me “Ketterman,” “Kiefelbaum,” “Kittiman,” and a dozen variations. He would put his hands on his hips and yell at me: “Kettner!”

Pedro showed his love by chopping people he loved down to size, because he knew we needed it. Pedro cared about people, people as they really are. He was a moral compass in a world where that’s become exquisitely rare. His phenomenal gift for understanding people, both overall and in the moment, gave him uncanny insights into the little lies we all tell ourselves, the fictions we build up as important in our lives. So, so often, he saw through that to the person we were trying to become, the life we were trying to lead, if only, if only. He was a master of helping us to see a version of ourselves that was a little better, a little truer, and how to get there. He did that for me. He did that for AJ Hinch when he was going through hell. He did it for Ron Washington when he was going through hell. Pedro did it for countless young people looking to him for inspiration and career advice. He did it, I’m guessing, for all of you here today, each and every one of you.

After my Zoom event, eleven days ago, I called Pedro back and we talked about the book we were writing together on baseball managers. I couldn’t wait to tell him about a new project.

“What are the two most beautiful words in sports?” I asked him, quoting Gomez to Gomez.

“Game 7,” he answered.

And what’s even more beautiful? “Overtime in Game 7.”

He did that Pedro thing: Oooooo, yeah, I like where you’re going. He loved the idea for a book, Overtime, about where the country is going with so much up in the air. He poured reverence into the words “Game 7” because he loved the drama and beauty and truth that came through in those little moments that turned games, and turned events, and turned life stories. He loved watching how people reacted under pressure. He loved how the action of the moment showed us who people really are.

We also talked about sportswriters and legacies. Not making this up. Unbelievable. I remember him getting into it and almost shouting— OK, maybe he was already shouting—“But what did you do? What will people remember you for?”

Pedro will be remembered by many, I think, as the heart and soul of baseball in this era, the man who loved the game and the people in the game with as much intensity and unwavering commitment and resourcefulness and infectious joy as anyone alive. That’s what countless baseball people have told me this last week and that’s what the outpouring of tributes reveals.

It reminds me of the death of a great friend Pedro and I shared, Ed Beitiks of the San Francisco Examiner. When Ed died, Examiner editor Phil Bronstein said at the time, it was like the soul of the paper had gone. Ed, Pedro and I spent an incredible season on the road together, and that year helped turn Pedro into the marvel of a man we all celebrate today. I’ve heard many people talk about how Pedro embodied a serene confidence, never showing the kind of self-doubt or crippling fear or insecurity that others had. I think it’s important to point out that he did have his insecurities, or once did, but came to understand they were beside the point. If you were true to the moment, if you were alert and alive to the pulsing human connection that made Pedro’s life so incredibly rich and vital, who had time to give a shit about any sense of insecurity or self-limitation? Just go with it, man.

Pedro and I for years tried to live by a code, a code we called KGB, for Kettmann Gomez Beitiks. Ed was fifty that year the three of us spent together on the road, and Pedro and I, the August ’62 boys, JFK babies, as he loved to say, were thirty-two. We’d never known anyone like Beitiks, but then who had? He grew up speaking Latvian in a displaced persons camp in Germany just after World War II, his mother and him relying on each other. When Ed spoke of the A Shau Valley in Vietnam, the images he shared haunted us. Ed was a philosophy major who could review books or compare cheap beer with the same gusto, a writer of peerless originality, precision and sheer overflowing glee, and he lived by a code, which he called the rules. He’d yell at us: “A man does not DO that!” We were an unlikely trio, Pedro the young Latin, me the pony-tailed former Berkeley English major, Ed with his round face and short gray hair the big riddle. People would come up to us in bars and restaurants and ask what our story was, and we’d tell them.

KGB to Pedro and I meant never tuning out that voice in your head, the voice that reminds you who you are. KGB was getting over yourself. KGB was being a fighter, ready to scrap, fearless until you weren’t, but KGB was also flying into Chicago a day early to soak up the city, an afternoon in the bleachers at Wrigley, Beitiks bursting out into show tunes to astonish a friendly waitress.

When I published an article in The New York Times in August 2000 with the headline “Baseball Must Come Clean on Its Darkest Secret,” and said what had to be said about steroids when no one was saying it, that was KGB. When Pedro—famously—used amazing quotes to go after Curt Schilling with a blistering column on the morning of Game 7 during the 2001 World Series, that was KGB, even if I was slow to see it. I was staying at the Gomez house and Sandi and I sat with Pedro just before he filed the piece, both of us telling him, “I don’t know about this.” The day of Game 7? Really? Pedro knew, and he was right. He earned a handshake from at least one Diamondback player the next day. He’d published the truth.

Pedro and I were still talking about the solemn importance of KGB up to two weeks ago, who was KGB, who wasn’t. We always hoped the people who weren’t KGB would become a little more that way, a little more soulful, a little more free, a little more willing to treat every moment on this earth as a chance to show us who they are. KGB was key in the ’90s for helping Pedro come into his own, but it was only a beginning.

A decade ago, I wrote a tribute to Pedro, trying to sum up all he’d taught me, and read it out loud to him, including the part about what I called The Gomez Rules. When I read it, it was like I was playing Sinatra, he was beaming with pleasure and couldn’t stop saying, “Oh man.”

HERE’S THAT EXCERPT:

Pedro Gomez was the one who turned me into a sportswriter. I spent two years as a traveling beat writer covering the local NHL team, the San Jose Sharks, for the San Francisco Chronicle, all the while thinking of myself as “not a sportswriter” and dreaming of an imminent move to Europe to write novels or something. When I switched from hockey to the baseball beat and met Pedro for the first time, I found his whole happy-Cuban thing grating. He just seemed too damn cheerful and too damn perfect, with his unflagging George Clooney smile, his beautiful and amazing Colombian wife, Sandi, a physical therapist, and above all his effortless reporting style. As it happened, Pedro found me grating, too, and made fun of what he saw as my whole angst-filled, pretentious-Berkeley, too-good-to-mix-with-other-sportswriters thing.

It was like love, the way Pedro and I fell into friendship. Almost by accident we ended up going to dinner in Arizona that first spring training and we couldn’t stop talking. That’s how the next three years went: Out most every night on the road, we would spend hours talking about baseball, writing and people. We both were fascinated by all the little details of how people really were, when you looked closer, from the heavy-perfume-wearing elevator operator at Tiger Stadium in Detroit with her syrupy voice and motherly concern to the A’s bullpen coach known as The Cave Man who toted around a black bag full of sex toys and had endless colorful tales to spin.

Pedro showed me how to be a sports reporter. I don’t know if I was too lazy before I met Pedro to do the job right or simply didn’t realize what I was missing, but he taught me a moral code for a beat writer:

GOMEZ RULE NO. 1: Don’t only talk to players when they do something wrong or hit the game-winning home run. If for example you notice a third baseman making a subtle but excellent play and happen to get a chance to ask about it, go talk to the guy on the night when everyone is talking to someone else. You do that partly to learn, since usually he’ll explain some aspect of the play you weren’t quite sure about, but also just to establish a dialogue, so that communication does not only come when you need something from him.

GOMEZ RULE NO. 2: Always go talk to the opposing manager, usually before the first game of the series. If you did it regularly, the other managers got to know you a little and usually appreciated the effort you made. We especially loved talking to Joe Torre, Lou Piniella and Phil Garner. Often they would give us scraps of insight that helped us understand the A’s. Plus, it was a blast.

GOMEZ RULE NO. 3: If you rip someone, always show up the next day, even (especially) if it’s your day off. They might want to curse you out. They might want to say you got something wrong—and might even have a point. They might just want to glare at you and make cracks about you from a distance. It doesn’t matter. Always show up.

GOMEZ RULE NO. 4: Keep your eyes open. Odd as it may sound, sportswriters even then often kept their heads down in the press box, typing away, checking stats, often muttering about their disgruntlement but not often truly focusing on what was happening on the field of play. They just looked up now and then to keep abreast of the basics. That meant they missed a lot. The fun part was the crazy little sequences you might never write about. Pedro and I both kept our eyes open and talked constantly about what we saw out there.

GOMEZ RULE NO. 5: Start every relationship you make on the assumption that someone is basically good, basically OK, and let them prove you wrong, rather than the opposite. From umpires to moody journeymen infielders to eccentric coaches, Pedro was consistent. His approach rubbed off.

GOMEZ RULE NO. 6: Always have fun out there. Always remember you’ve got a great job and look for ways to enjoy the hell out of it. This included things like leaving the press box for a few innings to watch the game from the front row at old Tiger Stadium, where it felt like the pop of a fastball getting swallowed up by the catcher’s mitt was exploding inside your head.

I think in one version of that text, I added a Gomez Rule No. 7 about all the other rules besides No. 6 being secondary, but I see now how they all fit together. I see now that as much as I celebrated what Pedro was trying to get across to me and so many others, as astonished as I was by the impact he had on me, I failed to grasp the scale of his influence. It’s not that I didn’t appreciate Pedro. KGB meant you tried, always, to shake yourself out of complacency, and I never for a second forgot how incredibly lucky I was to have such a great friend as Pedro so tuned in to me, so emotionally alive and so wise, there to help me through writing Juiced for Canseco, there as basically co-best man at my wedding, there, always, to give his take on a question I was turning over in my mind, which we’d think through together, adding flavor with our lexicon of favored phrases. “It was a rocket!” and “He showed tremendous stick-to-itiveness and “Nice toss, Golden Richards,” and, of course, “Was it over when the Germans bombed Pearl Harbor?”

Pedro thought in movie scenes and in thinking about him I keep flashing back to that John Cusack riff in the movie The Sure Thing where he talks about a guy named Nick. “Nick’s your buddy. Nick’s the kind of guy you can trust, drink a beer with.” That’s Pedro, our buddy, and it’s a little surreal to see this outpouring of love and respect for Pedro, ripples emanating out from a point in the middle, our Pedro, occasionally a goofball, interrupting himself with fits of laughter in the middle of a story he’s already told you eighty-three times, but also a truly beautiful soul, a man of courage and commitment so deep, it reached people who could not be reached.

Yesterday morning I called up Rob King, one of Pedro’s ESPN bosses. We’d never spoken before, but Pedro had told me all about Rob and what a good guy he is. In short, Rob and I were both part of what I call the Best Friends’ Club, the rich and vast network of people Pedro made feel so special, so loved and seen, we were all in a way his best friend, and by extension, all each other’s best friends. From Billy in Miami to T.J. in Teaneck to Bruce in Montara, and of course Bob and Charlie and Jose Joe and Willie and so, so many others, we were all connected, lit up on the map in an archipelago of love, of Pedro love.

As T.J. Quinn put it, Pedro’s life was a constant celebration of the people around him. And here’s Bruce Jenkins on Pedro: “Pure enthusiasm is such a treasure. Not the manufactured kind, summoned out of necessity, but a quality that defines a person right to the core. That’s how I’ll remember Pedro Gomez.”

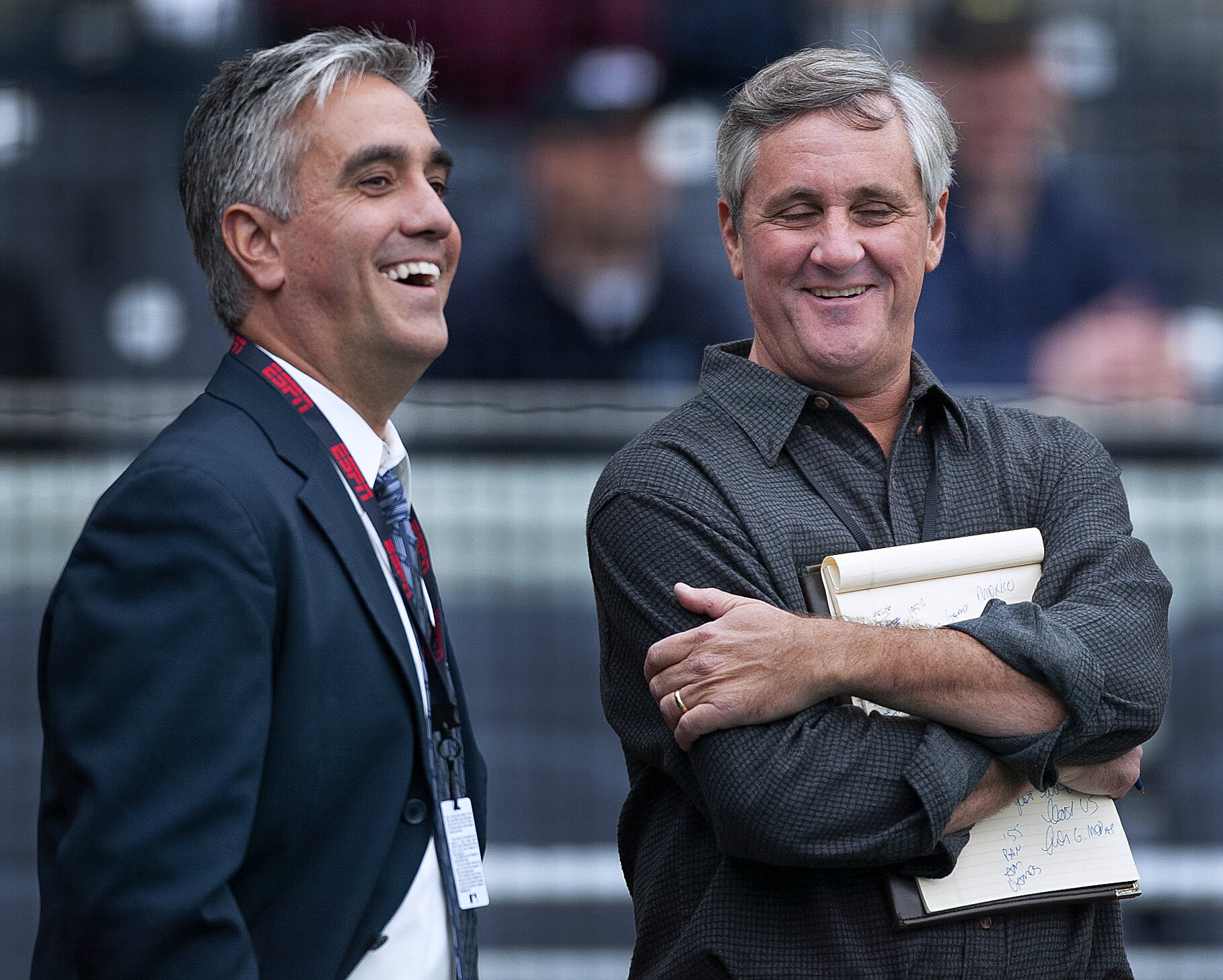

Pedro and Jenks. Photo by Brad Mangin

Rob King and I talked not like strangers, but more like brothers. Before long we were both in tears. I’ll admit I wasn’t so much pumping him for information as just trying to get through my morning. Rob talked about how there were no hollow interactions with Pedro, not ever, and professional roles didn’t matter, heart did, listening did, paying attention did. “In every face-to-face interaction we had,” Rob told me, “it was like going to home base, back to what mattered, back to who we have always been, even in this big, beautiful machine.”

That led me to share a few thoughts of my own and Rob almost gasped at one point.

“You just reminded me of something,” he said.

And he told me about the sign on the wall of his ESPN office, which reads: REMEMBER WHO YOU ARE. He told me how everyone who comes into the office comments on the sign, and how often he talks about it, but he never gets a chance to mention where the words came from. They came from Pedro. Rob’s first week at ESPN. Rob is going to write an essay about Pedro for a book we’re going to publish, tributes to Pedro from players and managers and writers and broadcasters, and we decided we’d title Rob’s essay, “Remember Who You Are.”

Half an hour later, I tried to reach Rob again to tell him that’s what we’re going to call the book in Pedro’s honor as well.

“It’s perfect,” T.J. told me on the phone. It gets it all. The pride in being Cuban. The focus on people. The high standards as a journalist, a friend and a man.

I texted Rob that we’d be using his title for the book, and he wrote back: “Oh my Lord. That’s amazing. Thank you for even thinking of that.”

Last month marked twenty years since Ed Beitiks died, and of course Pedro and I marked the occasion. We talked about how certain rare individuals, possessing a miraculous mix of qualities, live on among us in ways that are startling and beautiful and also, to be blunt, a little painful. I still hear Ed’s voice in my head all the time, talking to me, schooling me, laughing at me, and I know Pedro did as well. A book I wrote was optioned and I was hired to write up a treatment to turn it into a miniseries, and Pedro’s reaction was to shout, “Beitiks was right!” and then recite his favorite Ed quote, to me, “You’re so Hollywood it makes me sick!”

Pedro and I replayed our greatest hits over and over because they reminded us of who we are and made us, I hope, a little better. For Sandi and Rio and Dante and Sierra, Pedro’s presence isn’t going anywhere, it’s way too strong and vivid for that, and I know so many of you hear his voice in your ear, the way I do. For me, it’s Ketterman, don’t screw this up! And maybe, just maybe, I can use the rest of my days on this planet to try to live up to KGB. Maybe, just maybe, I can make Pedro proud, and maybe all of you can as well. Just remember who you are.

POSTSCRIPT

Picture editor Brad Mangin and I were thrilled that Terry Francona shared memories of growing up a Roberto Clemente fan (#46, “His Eyes Lit Up”), so we could include pictures of the great Clemente—which are, without doubt, essential to this book. For Pedro, nothing was more sacred than Clemente as a reference point, Clemente the player, attacking the game with what Pedro called “fury,” Clemente the trailblazer, “like a god” to all fans of Latin American background, Clemente the first Latin player voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Pedro was six when he fell deeply in love with baseball—in Spanish. This was in Detroit, where his family moved the year after he was born. His grandfather, born in Spain in 1899, worked as a Cuban Winter League umpire in Camaguey, and lived and breathed baseball. He would sit close to the radio, absorbed in Ernie Harwell’s game broadcast, despite the fact that he spoke zero English, having just fled Castro’s Cuba in 1967. Young Pedro would ask what had happened and his grandfather would recite every detail, explaining that Kah-LEEN-eh (Al Kaline, Pedro’s favorite player) had doubled in Jim Northrup and Willie Horton. Pedro’s grandfather understood the language of baseball.

In August 2018, Pedro posted on social media about his “abuelo from Camaguey,” Isaac Gonzalez, who “taught me to love baseball.” He told the following story: “My grandfather, a huge baseball fan, had just arrived from Cuba in ’67. We went to a game. A young couple in front of us was making out and not watching the game. He slapped the guy with his newspaper and told them in Spanish that they weren’t here for necking, to watch the game.”

His grandfather passed on his passion to young Pedro, whose fandom took deep hold in 1968 when the Tigers won 103 games and prevailed over Bob Gibson and the St. Louis Cardinals in a classic, seven-game World Series. Pedro never stopped hearing the echoes of his grandfather’s excited voice, talking about Kah-LEEN-eh and Mickey Esstanley, and never lost touch with his boyish enthusiasm for connecting with baseball simultaneously in two languages.

In the ’90s on the road together, Pedro and I spoke in Spanish often enough that I picked up a Cuban accent. We’d repeat expressions just for their music and flavor and beauty, like Spanish for unearned runs, at least in Pedro’s world, which was carreras sucias. Dirty runs. Pedro could talk for an hour about how much more evocative sucia was in that context than “unearned.” He especially loved talking about the Spanish (OK, Spanglish) for “rally killer,” which according to Pedro was mata rally. The verb matar in Spanish means “to kill,” yes, but it is also used for “massacre.” I still hear Pedro’s voice saying, “You didn’t just kill the rally, you massacred it!”

Baseball in Spanish transported Pedro even more than baseball in English, and it all connected with his conviction that Clemente played with “fury,” a simmering intensity that gave him an electric presence as a player. For Pedro and for me, there was no greater compliment than talking about going Clemente-in-the-corner. That meant going all out with a kind of mad intensity that fused into the poetic. Brad Mangin’s amazing work in putting together the pictures in this book helps us to see so much more, including Clemente’s fierce gaze. Brad went Clementein-the-corner on this book. So did the wide range of voices collected here, from brilliant writers’ writers to more plainspoken baseball men. I think it says a hell of a lot about Pedro and what he meant to people that he could inspire so many to open up and share such heartfelt glimpses.